| WILLIAM

C. BRUMFIELD

PHOTOGRAPHIC DOCUMENTATION OF ARCHITECTURAL MONUMENTS IN THE RUSSIAN NORTH:

VOLOGDA PROVINCE

Vologda Province, located some 400

kilometers northeast of Moscow, is one of the largest territories in European Russia, with

a size rivaling that of countries such as Hungary or Bulgaria. Although the province (or

oblast, as such administrative regions are known in Russian) is overwhelmingly rural, it

also contains a number of settlements whose historical references date as far back as the

twelfth century. The cultural and political center of this region is the city of Vologda,

the subject of my article "Photographic Documentation of Architectural Monuments in

the Russian North: Vologda, Visual Resources (Vol. 12, No. 2). But the historical,

cultural, and architectural legacy of this territory extends far beyond the city. The

present study is devoted to an analysis and photographic documentation of the primary

architectural monuments in the Vologda territory beyond Vologda itself.

With the rise of the Muscovite principality in the

fourteenth century and the establishment of a metropolitanate of the Orthodox Church in

Moscow itself, the church began to play an essential role for the advancement of Moscow's

position in this area of the north. In particular, the founding of monasteries by clerics

from Moscow's own monasteries provided not only places of spiritual refuge and retreat,

but also centers of Muscovite influence. The two most influential of these monastic

institutions, and the sites of the earliest extant masonry structures in the area, are the

St. Kirill Belozerskii Monastery, and the nearby Ferapontov Monastery (1). Both are located considerably to the north of Vologda, near

the confluence of the Sheksna River and the White Lake (Beloe ozero). This water network

connected the monasteries to the central regions of Muscovy, as well as to Vologda, and

endowed them with a strategic importance that aided their growth as Moscow's outposts.

The first monastery, formally dedicated to the Dormition of

the Virgin, was founded in 1397 on Siverskoe Lake, seven kilometers to the east of the

Sheksna River. Its founder, Kirill (Cyril; 1337-1427), was a monk of noble birth who had

served at the Simonov Monastery in Moscow and in 1390 became its hegumen. By leaving this

prestigious position and coming to the northern territory of Muscovy in 1397, he not only

achieved the ascetic life valued by the pioneers of Muscovite monasticism, but he also

furthered territorial claims of the Moscow grand prince. As one who frequently advised the

sons of Dmitrii Donskoi, Kirill was familiar with the political conditions that drove

Moscow's northern expansion. Indeed, the monastery's importance as both a religious center

and as an anchor of Muscovy's northern flank was recognized by the canonization of Kirill

in the fifteenth century and the naming of the entire monastic ensemble- consisting of two

adjacent monasteries, the Dormition and John the Baptist-for St. Kirill Belozerskii (2).

During the first century of its existence, the Dormition Monastery was built entirely of

logs, but in the summer of 1496 a master builder from Rostov known as Prokhor, along with

twenty masons, rebuilt in brick the main monastery church, dedicated to the Dormition (Photo 1, 2). In view of its remote location, the

Dormition Cathedral is not among Russia's largest, nor was its design comparable to major

Muscovite churches erected under the supervision of Italian architects arriving in Moscow

in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, during the reigns of Ivan III (the

Great) and Vasilii III (3).

Instead, the form of the Dormition Cathedral resembles that

of the more primitive limestone Muscovite churches of the late fourteenth century.

However, brick had by now become the primary building material of masonry churches,

although carved limestone blocks were still used for details, such as the perspective

portals on the north, west, and south facades. The Dormition Cathedral has a

cross-inscribed plan with four piers supporting corbelled arches leading to a single drum

and cupola. The apsidal structure was divided into three parts, each of which had a

separate sloped roof in a halved conical shape. The upper walls originally culminated in

at least two, and probably three, rows of decorative gables known as kokoshniki (4). Other exterior decorative elements, such as terra cotta

balusters set in an ornamental band at the top of the walls, resemble fifteenth-century

Muscovite details. In the sixteenth through the eighteenth centuries the church underwent

several modifications, including the construction of three attached churches (a typical

occurrence in medieval Russia): the diminutive Church of St. Vladimir (1554), the Church

of St. Epifanii of Cyprus (built in 1645 on the north facade of the Vladimir Church for

use as a burial chapel for the Teliatevskii princely family); and at the southeast corner

of the Dormition Cathedral, a church dedicated to St. Kirill (constructed in 1585 over the

site of his burial and rebuilt in 1781-84) ( Photos 3, 4, 5).

Other additions to the Dormition Cathedral include a parvis

built along the north and west walls at the end of the sixteenth century. The north parvis

was rebuilt in the seventeenth century, and the one on the west disappeared entirely with

the building of a much larger, awkward entrance structure in 1791. Perhaps the most

destructive changes occurred in the eighteenth century, when the kokoshniki of the upper

structure were replaced with a four-sloped roof. Despite these changes, the basic form of

the original cathedral has survived, and provides much information on the building and

design capabilities of northern masons at the turn of the sixteenth century.

As the sixteenth century progressed the St. Kirill Belozerskii Monastery received major

donations that made it one of the largest such institutions in Russia, second in size only

to the Trinity-St. Sergius Monastery near Moscow. In 1519 the monastery refectory and its

attached Church of the Presentation of the Virgin were rebuilt in brick. The church itself

is situated at the eastern end of the refectory axis, with a polygonal east wall elevated

on a high socle and originally culminating in rows of kokoshniki, over which was a single

brick drum and cupola (Photo 27). The interior of the church was

cruciform in shape, with a groin vault. Unfortunately, the original vaults and upper

structure disappeared with subsequent rebuilding, but the height of the east wall suggests

an early development in the design of tower churches that would play such a distinctive

role in sixteenth-century Muscovite architecture.

As the sixteenth century progressed the St. Kirill Belozerskii Monastery received major

donations that made it one of the largest such institutions in Russia, second in size only

to the Trinity-St. Sergius Monastery near Moscow. In 1519 the monastery refectory and its

attached Church of the Presentation of the Virgin were rebuilt in brick. The church itself

is situated at the eastern end of the refectory axis, with a polygonal east wall elevated

on a high socle and originally culminating in rows of kokoshniki, over which was a single

brick drum and cupola (Photo 27). The interior of the church was

cruciform in shape, with a groin vault. Unfortunately, the original vaults and upper

structure disappeared with subsequent rebuilding, but the height of the east wall suggests

an early development in the design of tower churches that would play such a distinctive

role in sixteenth-century Muscovite architecture.

The next two brick churches of the St. Kirill Monastery are

in somewhat better condition, although they too have suffered from later modifications.

The Church of the Archangel Gabriel was constructed in 1531 34 with support provided by

Vasilii III, grand prince of Moscow, who in 1528 had made a pilgrimage to the monastery

with his second wife, Elena Glinskaia, to pray for the birth of a male heir (Photos 28, 29, 30, 41). Situated near the southwest corner of the Dormition Cathedral, the

Archangel Church has a cross-inscribed plan, with four interior piers and a tripartite

apsidal structure. The high walls of the main cube concluded not in zakomary, but in a row

of bell gables (not preserved), behind which were two ascending rows of kokoshniki (5) (Semicircular gable ends at the top of walls are called

zakomary and play a role in supporting the superstructure; kokoshniki are primarily

ornamental).

The second of the churches commissioned by Vasilii III at the monastery was dedicated to

John the Baptist. Also built in 1531-34, it shares certain stylistic features with the

Archangel Gabriel Church, including a roofline that originally culminated in kokoshniki (Photos 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 39). Situated beyond the original Dormition

Monastery walls near a small chapel erected by St. Kirill, this church became the nucleus

of a "small" (malyi) Monastery of John the Baptist that complemented the

Dormition to form the ensemble of St. Kirill Belozerskii Monastery. Because of

similarities in style and date of construction for the Archangel and John the Baptist

churches, some Russian specialists consider them to be the work of one architect-possibly

Grigorii Borisov from Rostov (6).

The second of the churches commissioned by Vasilii III at the monastery was dedicated to

John the Baptist. Also built in 1531-34, it shares certain stylistic features with the

Archangel Gabriel Church, including a roofline that originally culminated in kokoshniki (Photos 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 39). Situated beyond the original Dormition

Monastery walls near a small chapel erected by St. Kirill, this church became the nucleus

of a "small" (malyi) Monastery of John the Baptist that complemented the

Dormition to form the ensemble of St. Kirill Belozerskii Monastery. Because of

similarities in style and date of construction for the Archangel and John the Baptist

churches, some Russian specialists consider them to be the work of one architect-possibly

Grigorii Borisov from Rostov (6).

Other churches erected at the Kirillov Monastery during the

late sixteenth century include the Gate Church of St. John Climacus (Photos

22, 23, 24, 25),

which provides an imposing entrance to the monastery complex. The function of the

monastery as a fortress was severely tested at the beginning of the seventeenth century,

during the "Time of Troubles". Although the monastery withstood a .prolonged

siege, the surrounding villages--so necessary for the support of the monastery, were

severely damaged. During the second half of the seventeenth century, Muscovite rulers, and

particularly Tsar Aleksei Mikhailovich, decided to reinforce the monstery walls against

another possible attack from the north and west. The current massive walls--although never

tested in battle--are among the last great works of medieval Russian masonry architecture

(Photos 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12,

13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 26, 38).

The earliest extant masonry church in the Sheksna-White

Lake region is located in the second of the area's monastic institutions, the Monastery of

the Nativity of the Virgin, founded in 1398 on the shores of Lake Borodava some twenty

kilometers northeast of the St. Kirill Belozerskii monastery ensemble (40,

42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48). Its founder, Ferapont (1337-1426), had also been a monk at

Moscow's Simonov Monastery, and had accompanied Kirill on his journey to the north (7). Within a year of the establishment of the Dormition

Monastery on Siverskoe Lake, Ferapont left to form his own spiritual retreat. Like Kirill,

Ferapont was of noble birth and well acquainted with the power structure of the Muscovite

state. Ferapont was canonized in the sixteenth century, and the northern monastery that he

founded came to be known as the Ferapontov, while retaining its original dedication to the

Nativity of the Virgin.

The monastery's first masonry structure, the brick Cathedral of the Nativity of the

Virgin, was built in 1490, six years earlier than the Dormition Cathedral at the St.

Kirill Monastery. Both churches share a relatively simple cross-inscribed plan, with four

piers and a single drum and cupola. The Nativity is smaller, but shows a greater

refinement of proportions, in part because of its elevation on a raised base, or podklet (Photo 49, 50). Like the Dormition Cathedral at

St. Kirill Monastery, the upper walls of the Nativity Cathedral were substantially

modified from the sixteenth through the eighteenth centuries, but they originally led to

three rows of decorative, ogival kokoshniki, the first row of which was a direct extension

of the walls.

The monastery's first masonry structure, the brick Cathedral of the Nativity of the

Virgin, was built in 1490, six years earlier than the Dormition Cathedral at the St.

Kirill Monastery. Both churches share a relatively simple cross-inscribed plan, with four

piers and a single drum and cupola. The Nativity is smaller, but shows a greater

refinement of proportions, in part because of its elevation on a raised base, or podklet (Photo 49, 50). Like the Dormition Cathedral at

St. Kirill Monastery, the upper walls of the Nativity Cathedral were substantially

modified from the sixteenth through the eighteenth centuries, but they originally led to

three rows of decorative, ogival kokoshniki, the first row of which was a direct extension

of the walls.

The most extensively decorated part of the exterior is the

west facade. Although it is now covered by an elevated porch, or parvis, constructed

around the middle of the sixteenth century, this facade had an ornamental ceramic strip

above the socle (podklet), and the zakomary were filled with decorative brick patterns in

the style of fourteenth-century brick churches in Pskov (8).

In their original form both the Dormition and Nativity Cathedrals apparently culminated in

a simple low cupola, replaced in the eighteenth century with a hypertrophied,

double-tiered baroque cupola. According to archival documents the cupola of the Nativity

Cathedral was originally covered in "white iron" (tin), which was replaced in

the early eighteenth century with wooden shingles. The current dome and the conversion of

the kokoshniki into a four-sloped roof appeared in 1794-97 (9).

The west portal was framed with ogival perspective arches of molded brick and was

surrounded by frescoes devoted to the Nativity of the Virgin Mary. Although partially

damaged by the construction of the parvis in the sixteenth century, the frescoes were

afforded a greater measure of protection from the climate by that same construction, and

they have survived relatively intact. They are, in fact, excellent examples of the work of

one of the most important medieval Russian artists, Dionisii, who with the assistance of

his two sons painted the interior of the Nativity Cathedral in 1502 (10). The fact that such a renowned artist, accustomed to

commissions for frescoes and icons from the court of Grand Prince Ivan III/ should engage

in extensive work far to the north is further evidence of the close relations between

these monasteries and the center of political and ecclesiastical power in Moscow. Indeed/

the hegumen who commissioned the rebuilding of the church in brick and the painting of the

frescoes was Ioasaf/ former archbishop of Rostov and a member of one of Russia's most

prominent noble families/ the Obolenskiis.

The west portal was framed with ogival perspective arches of molded brick and was

surrounded by frescoes devoted to the Nativity of the Virgin Mary. Although partially

damaged by the construction of the parvis in the sixteenth century, the frescoes were

afforded a greater measure of protection from the climate by that same construction, and

they have survived relatively intact. They are, in fact, excellent examples of the work of

one of the most important medieval Russian artists, Dionisii, who with the assistance of

his two sons painted the interior of the Nativity Cathedral in 1502 (10). The fact that such a renowned artist, accustomed to

commissions for frescoes and icons from the court of Grand Prince Ivan III/ should engage

in extensive work far to the north is further evidence of the close relations between

these monasteries and the center of political and ecclesiastical power in Moscow. Indeed/

the hegumen who commissioned the rebuilding of the church in brick and the painting of the

frescoes was Ioasaf/ former archbishop of Rostov and a member of one of Russia's most

prominent noble families/ the Obolenskiis.

Due to the remote location of the small Ferapontov Monastery/ the frescoes on both

interior and exterior of the Nativity Cathedral were not frequently overpainted and are

relatively well preserved/ despite modifications to the structure of the church. These

changes include not only the addition of the parvis on the north/ west and south sides/

but also the construction of two attached churches: the Church of the Annunciation (1530

31; see below), and the Church of St. Martinian (1640), with its tent tower. On the west

side/ the ensemble is linked by a raised gallery/ which extends from the parvis to the

Annunciation Church/ with a seventeenth-century bell tower situated near the midpoint (Photo 51, 52, 53, 54).

Due to the remote location of the small Ferapontov Monastery/ the frescoes on both

interior and exterior of the Nativity Cathedral were not frequently overpainted and are

relatively well preserved/ despite modifications to the structure of the church. These

changes include not only the addition of the parvis on the north/ west and south sides/

but also the construction of two attached churches: the Church of the Annunciation (1530

31; see below), and the Church of St. Martinian (1640), with its tent tower. On the west

side/ the ensemble is linked by a raised gallery/ which extends from the parvis to the

Annunciation Church/ with a seventeenth-century bell tower situated near the midpoint (Photo 51, 52, 53, 54).

In addition to the two churches endowed by Vasilii III at

St. Kirill Monastery/ the grand prince commissioned a third/ at Ferapontov Monastery/ as

part of the same votive offering. There has been some uncertainty as to the precise dates

of construction for the Refectory Church of the Annunciation/ but recent research

indicates that it was built in 1530-31/ again possibly by Grigorii Borisov." As at

the St. Kirill Monastery/ the church and refectory were elevated on a podklet, with the

church extending on the east. In a design common to northern monasteries/ the refectory

church was heated by air ducts from the scullery stoves located on the ground floor/ or

podklet.

Because of its modest size/ the Annunciation Church has no

interior piers. Yet the vertical development is increased through a second tier/ whose

interior is in the shape of a cylinder/ with small chambers attached. On the north and

east sides/ the exterior walls of the chambers form bell gables/ a device also used in the

Archangel Gabriel Church. Above the second tier are three rows of kokoshniki (recently

restored) and a drum with cupola.

During the five decades after the completion of the three churches donated by Vasilii III

at the St. Kirill and Ferapontov Monasteries construction began on other masonry churches

throughout the Vologda and White Lake territories. In the immediate area of Vologda the

earliest significant masonry structure is the Cathedral of the Savior at the

Savior-Prilutskii Monastery. Established in 1371, the Savior-Prilutskii Monastery was

supported by Moscow's grand prince Dmitrii Ivanovich (Donskoi) as one of the first

bulwarks of Orthodox Moscow in the rich but difficult terrain surrounding Vologda (12). The original buildings, including the main church, were of

logs. After its destruction by fire, the Cathedral of the Savior was rebuilt in brick

during 1537-42 with substantial support from Moscow, including a decree issued in 1541 by

the young Ivan IV releasing the monastery from all taxes for a period of five years.

Larger than the cathedrals at St. Kirill and Ferapontov Monasteries, the Savior Cathedral

is similar to other major monastery churches whose design derived from the main Kremlin

cathedrals. At the same time, it displays distinctive elements that link it to its

northern predecessors.

During the five decades after the completion of the three churches donated by Vasilii III

at the St. Kirill and Ferapontov Monasteries construction began on other masonry churches

throughout the Vologda and White Lake territories. In the immediate area of Vologda the

earliest significant masonry structure is the Cathedral of the Savior at the

Savior-Prilutskii Monastery. Established in 1371, the Savior-Prilutskii Monastery was

supported by Moscow's grand prince Dmitrii Ivanovich (Donskoi) as one of the first

bulwarks of Orthodox Moscow in the rich but difficult terrain surrounding Vologda (12). The original buildings, including the main church, were of

logs. After its destruction by fire, the Cathedral of the Savior was rebuilt in brick

during 1537-42 with substantial support from Moscow, including a decree issued in 1541 by

the young Ivan IV releasing the monastery from all taxes for a period of five years.

Larger than the cathedrals at St. Kirill and Ferapontov Monasteries, the Savior Cathedral

is similar to other major monastery churches whose design derived from the main Kremlin

cathedrals. At the same time, it displays distinctive elements that link it to its

northern predecessors.

The cathedral walls support two rows of curved structural gables, or zakomary, leading to

a clearly spaced ensemble of five drums and cupolas. The upper parts of the drums show

ornamental brickwork in the Pskov style, which had been assimilated throughout Muscovy in

the fifteenth century, although not in the Kremlin cathedrals. The main cupola, much

larger than the flanking four, creates a strong vertical point to the pyramidal shape. The

height of the structure is increased by a podklet, or socle, which contained a separate

church for use primarily in the winter (a feature typical of Muscovite churches). The

interior of the Savior Cathedral, whose white-washed walls were never painted with

frescoes, possesses an austere monumentality displayed in the ascent from the four piers

to the corbelled, vaults (reflected in the exterior zakomary) that support the cupola

drums. The vaulting is reinforced with iron tie rods. A raised gallery attached to the

north, west, and south facades leads on the southeast corner to a refectory and Church of

the Presentation, built in the late 1540s in a style similar to the refectory churches at

St. Kirill and Ferapontov monasteries, with a roof of decorative kokoshniki ascending to a

single cupola. The ensemble is completed by a bell tower, rebuilt in 1729-30 on a

seventeenth-century base.

The cathedral walls support two rows of curved structural gables, or zakomary, leading to

a clearly spaced ensemble of five drums and cupolas. The upper parts of the drums show

ornamental brickwork in the Pskov style, which had been assimilated throughout Muscovy in

the fifteenth century, although not in the Kremlin cathedrals. The main cupola, much

larger than the flanking four, creates a strong vertical point to the pyramidal shape. The

height of the structure is increased by a podklet, or socle, which contained a separate

church for use primarily in the winter (a feature typical of Muscovite churches). The

interior of the Savior Cathedral, whose white-washed walls were never painted with

frescoes, possesses an austere monumentality displayed in the ascent from the four piers

to the corbelled, vaults (reflected in the exterior zakomary) that support the cupola

drums. The vaulting is reinforced with iron tie rods. A raised gallery attached to the

north, west, and south facades leads on the southeast corner to a refectory and Church of

the Presentation, built in the late 1540s in a style similar to the refectory churches at

St. Kirill and Ferapontov monasteries, with a roof of decorative kokoshniki ascending to a

single cupola. The ensemble is completed by a bell tower, rebuilt in 1729-30 on a

seventeenth-century base.

The line of development represented by the three main monastery churches-(in Russian,

sobor, or "cathedral")-discussed above would lead to the Cathedral of St. Sophia

in Vologda, built in 1568-70 to a design based on the Dormition Cathedral in the Moscow

Kremlin (13). During the same period, Anika Strogranov,

founder of the most dynamic branch of the Stroganov dynasty, endowed the Church of the

Annuncation (1560 early 1570s) at Solvychegodsk, the center of the family's commercial

empire on the Vychegda River (14). A century later, Grigorii

Stroganov supported the rebuilding in brick of the cathedral of the Presentation Monastery

(1688-1690s). These two churches are important examples of late medieval architecture in

the Russian north, but they are situated in what is now Arkhangelsk province, beyond the

already extensive limits defined at the beginning of this article.

The line of development represented by the three main monastery churches-(in Russian,

sobor, or "cathedral")-discussed above would lead to the Cathedral of St. Sophia

in Vologda, built in 1568-70 to a design based on the Dormition Cathedral in the Moscow

Kremlin (13). During the same period, Anika Strogranov,

founder of the most dynamic branch of the Stroganov dynasty, endowed the Church of the

Annuncation (1560 early 1570s) at Solvychegodsk, the center of the family's commercial

empire on the Vychegda River (14). A century later, Grigorii

Stroganov supported the rebuilding in brick of the cathedral of the Presentation Monastery

(1688-1690s). These two churches are important examples of late medieval architecture in

the Russian north, but they are situated in what is now Arkhangelsk province, beyond the

already extensive limits defined at the beginning of this article.

In fact Solvychegodsk is situated only some ninety

kilometers north of the town of Velikii Ustiug which anchors the northeast corner of the

Vologda region and comprises a major architectural ensemble in its own right. The terrain

is defined by the confluence of two large rivers, the Sukhona and the lug, which merge to

form a third-the Northern Dvina (15). This network of three

navigable rivers formed part of a transportation network that attracted the earliest

Russian settlers there, apparently by the middle of the twelfth century. The mercantile

city of Novgorod sent its traders to the region, and until the middle of the fifteenth

century, Novgorod lay claim to authority over the area. Velikii Ustiug ultimately cast its

lot with Moscow, however, and became an important military post for the expanding

Muscovite state. Despite the severe northern climate and the great distances between major

settlements, Ustiug thrived in the sixteenth century, particularly with the development of

trade between Russia and England and Holland during the reign of Ivan the Terrible.

Like most northern towns, Ustiug was built almost entirely of wood, and fire was a

constant menace. As a result there are no surviving churches before the middle of the

seventeenth century. As trade with western Europe expanded in the seventeenth century,

Ustiug's merchants and churches acquired wealth that created some of the town's early

brick churches. The main cathedral, dedicated to the Dormition of Mary, was built in brick

during the 1550s, but had to be rebuilt a century later, after a major fire damaged the

walls. Funds to complete the reconstruction were provided by Tsar Aleksei Mikhailovich and

by the Bosykh family, local merchants of considerable wealth. In the eighteenth century,

the cathedral was modified still further. It is now flanked by three other churches, of

which the most impressive is the Cathedral of St. Procopius of Ustiug, built in 1668 (16). These churches are now being returned to active parish

use, although I was told that many problems of restoration and maintenance remain.

Like most northern towns, Ustiug was built almost entirely of wood, and fire was a

constant menace. As a result there are no surviving churches before the middle of the

seventeenth century. As trade with western Europe expanded in the seventeenth century,

Ustiug's merchants and churches acquired wealth that created some of the town's early

brick churches. The main cathedral, dedicated to the Dormition of Mary, was built in brick

during the 1550s, but had to be rebuilt a century later, after a major fire damaged the

walls. Funds to complete the reconstruction were provided by Tsar Aleksei Mikhailovich and

by the Bosykh family, local merchants of considerable wealth. In the eighteenth century,

the cathedral was modified still further. It is now flanked by three other churches, of

which the most impressive is the Cathedral of St. Procopius of Ustiug, built in 1668 (16). These churches are now being returned to active parish

use, although I was told that many problems of restoration and maintenance remain.

Despite the current difficult economic situation, progress in preserving the historic

architecture of Ustiug is clearly visible. The oldest structure to survive in its original

form is the Church of the Ascension, built in 1648-49 in the style of a Moscow parish

church, with a highly ornamented, asymmetrical grouping of volumes. The Church of St.

Nicholas Gostunskii (late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries), with its remarkable

detached bell tower, shows a greater precision of form. The low-relief, scrolled baroque

ornament on the tower is traced in black in a manner reminiscent of the town's most famous

craft technique-niello. Two decades ago this church was still being used as a saw mill

because of its location on the bank of the Sukhona River. It has since been restored on

the exterior, and is now used as a gallery to display the work of local painters (17).

Despite the current difficult economic situation, progress in preserving the historic

architecture of Ustiug is clearly visible. The oldest structure to survive in its original

form is the Church of the Ascension, built in 1648-49 in the style of a Moscow parish

church, with a highly ornamented, asymmetrical grouping of volumes. The Church of St.

Nicholas Gostunskii (late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries), with its remarkable

detached bell tower, shows a greater precision of form. The low-relief, scrolled baroque

ornament on the tower is traced in black in a manner reminiscent of the town's most famous

craft technique-niello. Two decades ago this church was still being used as a saw mill

because of its location on the bank of the Sukhona River. It has since been restored on

the exterior, and is now used as a gallery to display the work of local painters (17).

Further

to the south along the Sukhona is the late baroque Church of St. Simeon the Stylite

(1760s), which also has a large, free-standing bell tower near its northwest corner. The

design of the church is heavily derived from Petersburg architecture of the reign of

empress Elizabeth. Like much of the central part of Ustiug, the west facade of this church

forms a picturesque silhouette when seen from the river. The eastern approach, however,

has an appearance of its own, with lanes that wander between small wooden houses and

gardens. In such areas one has a sense of what the town might have looked like in the

eighteenth century. Further

to the south along the Sukhona is the late baroque Church of St. Simeon the Stylite

(1760s), which also has a large, free-standing bell tower near its northwest corner. The

design of the church is heavily derived from Petersburg architecture of the reign of

empress Elizabeth. Like much of the central part of Ustiug, the west facade of this church

forms a picturesque silhouette when seen from the river. The eastern approach, however,

has an appearance of its own, with lanes that wander between small wooden houses and

gardens. In such areas one has a sense of what the town might have looked like in the

eighteenth century.

Although the development of St. Petersburg in the eighteenth century lessened the

importance of Ustiug as a center of transportation and trade, it continued to prosper as a

mercantile center and became renowned as a center of crafts such as leather and metal

working, as well as the production of fine enamel objects. In particular its silversmiths

developed special skills in the niello technique, and their work was in demand not only in

the north but in St. Petersburg and the imperial court. Although never a major city,

Ustiug's prosperity was reflected in the increasing number of its masonry houses, a number

of which have been preserved along the river embankment and along Uspenskaia (Dormition)

Street, roughly parallel to the river.

Although the development of St. Petersburg in the eighteenth century lessened the

importance of Ustiug as a center of transportation and trade, it continued to prosper as a

mercantile center and became renowned as a center of crafts such as leather and metal

working, as well as the production of fine enamel objects. In particular its silversmiths

developed special skills in the niello technique, and their work was in demand not only in

the north but in St. Petersburg and the imperial court. Although never a major city,

Ustiug's prosperity was reflected in the increasing number of its masonry houses, a number

of which have been preserved along the river embankment and along Uspenskaia (Dormition)

Street, roughly parallel to the river.

The wealth of local

merchants led to yet another series of donations to monastery churches, some of which

gained elaborate gilded iconostases that reveal a northern interpretation of European

baroque art. One of the best examples is Trinity Cathedral at the Trinity-Gleden

Monastery. Although visible from Velikii Ustiug, the monastery is situated some five

kilometers to the southwest on the opposite bank of the Sukhona. Established no later than

the middle of the thirteenth century, the monastery consisted entirely of wooden

structures, including three log churches, for the first four centuries of its existence (18). Its earliest masonry structure is the rebuilt Trinity

Cathedral, begun in 1659 with the support of donations by Sila and Ivan Grudtsyn, members

of one of Ustiug's wealthiest merchant families. Subsequent financial and legal

difficulties after the death of the brothers halted construction for much of the 1660s

until 1690. The structure was finally completed only at the end of the seventeenth century

(19). The wealth of local

merchants led to yet another series of donations to monastery churches, some of which

gained elaborate gilded iconostases that reveal a northern interpretation of European

baroque art. One of the best examples is Trinity Cathedral at the Trinity-Gleden

Monastery. Although visible from Velikii Ustiug, the monastery is situated some five

kilometers to the southwest on the opposite bank of the Sukhona. Established no later than

the middle of the thirteenth century, the monastery consisted entirely of wooden

structures, including three log churches, for the first four centuries of its existence (18). Its earliest masonry structure is the rebuilt Trinity

Cathedral, begun in 1659 with the support of donations by Sila and Ivan Grudtsyn, members

of one of Ustiug's wealthiest merchant families. Subsequent financial and legal

difficulties after the death of the brothers halted construction for much of the 1660s

until 1690. The structure was finally completed only at the end of the seventeenth century

(19).

The cathedral's design and exterior form owe much to the slightly earlier Cathedral of the

Archangel Michael (1653-56) at the monastery of the same name in Ustiug itself. Both are

elevated on a high socle or base; both have walls that rise to a cornice underlying the

curved gable ends, or zakomary (a distant derivation from early Italian influence, such as

the Archangel Michael Cathedral in the Moscow Kremlin); and each has a level, four-sloped

roof placed over the zakomary (as opposed to a roofline following the contours of the

curved gables) (20). Each also has a raised porch, or parvis,

attached to all but the east facade. But the major difference between the two main

monastery cathedrals of Velikii Ustiug concerns the interior structure. The Archangel

Michael Cathedral has four piers, in the traditional inscribed-cross arrangement. In

contrast, the Trinity Cathedral has two piers in a plan that resembles the Solvychegodsk

Annunciation Cathedral of a century earlier.

The cathedral's design and exterior form owe much to the slightly earlier Cathedral of the

Archangel Michael (1653-56) at the monastery of the same name in Ustiug itself. Both are

elevated on a high socle or base; both have walls that rise to a cornice underlying the

curved gable ends, or zakomary (a distant derivation from early Italian influence, such as

the Archangel Michael Cathedral in the Moscow Kremlin); and each has a level, four-sloped

roof placed over the zakomary (as opposed to a roofline following the contours of the

curved gables) (20). Each also has a raised porch, or parvis,

attached to all but the east facade. But the major difference between the two main

monastery cathedrals of Velikii Ustiug concerns the interior structure. The Archangel

Michael Cathedral has four piers, in the traditional inscribed-cross arrangement. In

contrast, the Trinity Cathedral has two piers in a plan that resembles the Solvychegodsk

Annunciation Cathedral of a century earlier.

The use of the two-piered plan, when implemented with

careful calculation of the stress on the exterior walls of large structures such as the

Trinity Cathedral, permits a significantly greater illumination of the interior. The piers

are relatively compact, as are the spring arches of the vaulting. In addition, all of the

five drums are situated over the main interior space. In the typical design of earlier

medieval churches, the east drums were placed over bays located behind the iconostasis,

thus diminishing the amount of light cast on the main interior space. By the seventeenth

century, icon screens were more frequently attached to the upper part of the east wall

(above the opening for the eastward projection of the apse) in a design that allowed more

light in the main space.

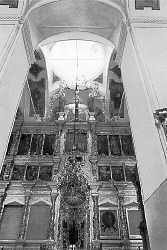

Taken together, these factors permit a greater natural illumination of the interior of the

Trinity Cathedral and its iconostasis, which is one of the most elaborate in the Russian

north. It should be noted that the interior walls of the cathedral were not painted with

frescoes and the main icon screen, consisting of five rows of intricately carved, gilded

wood, was erected only in 1776-84. In a departure from typical practice, the iconostasis

contains extensive statuary that amplifies the central iconic motif of the ministry and

Passion of Christ. The ultimate sources for this peculiar eighteenth-century combination

of florid baroque and neoclassical elements are St. Petersburg and, possibly, the

Ukrainian baroque. However, the Trinity Monastery contract with the master craftsmen

informs that they were from the town of Totma/ also located on the Sukhona River, some 200

kilometers to the southwest of Velikii Ustiug (21). During

the eighteenth century the town of Totma, whose wealth was based on salt refining and

trade on the northern river network, supported a flourishing baroque style in church

architecture and decoration, and it is here that our architectural survey of the Vologda

region will conclude.

Taken together, these factors permit a greater natural illumination of the interior of the

Trinity Cathedral and its iconostasis, which is one of the most elaborate in the Russian

north. It should be noted that the interior walls of the cathedral were not painted with

frescoes and the main icon screen, consisting of five rows of intricately carved, gilded

wood, was erected only in 1776-84. In a departure from typical practice, the iconostasis

contains extensive statuary that amplifies the central iconic motif of the ministry and

Passion of Christ. The ultimate sources for this peculiar eighteenth-century combination

of florid baroque and neoclassical elements are St. Petersburg and, possibly, the

Ukrainian baroque. However, the Trinity Monastery contract with the master craftsmen

informs that they were from the town of Totma/ also located on the Sukhona River, some 200

kilometers to the southwest of Velikii Ustiug (21). During

the eighteenth century the town of Totma, whose wealth was based on salt refining and

trade on the northern river network, supported a flourishing baroque style in church

architecture and decoration, and it is here that our architectural survey of the Vologda

region will conclude.

The first recorded reference to Totma is 1137-ten years

earlier than Moscow. During the sixteenth century it became a major center of salt

refining, which brought considerable wealth to local monasteries and to a branch of the

Stroganov family, who rapidly gained control of this enterprise. In addition Totma's

prosperity increased not only through its position on the trading route to the White Sea,

but also through trade with Siberia. Both Ivan the Terrible and Peter the Great visited

Totma, which provides further evidence of its importance to the commerce of the Russian

north. Certain local merchants showed remarkable enterprise in exploring distant terrain,

and by the end of the eighteenth century, a number of expeditions to Alaska were funded in

Totma. Indeed, a Totma resident named Ivan Kuskov founded California's Fort Ross in 1812 (22). His log-house in Totma has been converted into a modest,

but attractive museum.

The wealth that flowed into this community during the

eighteenth century supported the building of a number of brick churches of striking

design, with large bell towers and baroque decoration in a distinctive scroll pattern

formed by low brick relief. These churches, and the nearby Savior-Sumorin Monastery, were

designed to present an imposing view to the river, rising as they did above the wooden

settlements around them. Fortunately, a few of these landmarks are being restored-in some

cases for use by the Orthodox Church and in others as sites for museums. However, the

restoration proceeds sporadically, and petty vandalism has undone some of the repairs.

The most imposing of the monuments is the Church of the Entry into Jerusalem, built in

1774-94 with funds provided by the brothers Grigorii and Peter Panov, merchants who were

involved in the trade with "Russian America"(23)

Churches of this type in Totma were designed without interior piers, and their height was

dictated not only by aesthetic considerations, but also by the fact that they actually

consisted of two churches, the lower of which was used in winter and the upper in the

summer. The narrow pilasters that segment the facade and emphasize its height, the

elaborate scroll work between the window courses, and the detailing of the cornice and

cupola drums are executed with a remarkable sense of proportion. The bell tower attached

to the vestibule in the west echoes the vertical accent of the main structure.

The most imposing of the monuments is the Church of the Entry into Jerusalem, built in

1774-94 with funds provided by the brothers Grigorii and Peter Panov, merchants who were

involved in the trade with "Russian America"(23)

Churches of this type in Totma were designed without interior piers, and their height was

dictated not only by aesthetic considerations, but also by the fact that they actually

consisted of two churches, the lower of which was used in winter and the upper in the

summer. The narrow pilasters that segment the facade and emphasize its height, the

elaborate scroll work between the window courses, and the detailing of the cornice and

cupola drums are executed with a remarkable sense of proportion. The bell tower attached

to the vestibule in the west echoes the vertical accent of the main structure.

The nearby Church of the Nativity of Christ shows similar decorative and structural

features, but its general appearance is quite different. Instead of the traditional five

cupolas with a bell tower in the west, the structure is highly centralized, with an

elongated series of octagons rising above the main structure in the manner of a spire. The

refectory and porch are modest in comparison with this soaring vertical emphasis. Of

special interest is the fact that this building, like a number of other eighteenth-century

masonry churches in Totma, was constructed in the two phases: the lower, winter church was

built in 1746-48, and the upper church was added in 1786-93. The lower church thus serves

as a base for the great height of the upper church; but the design is so accomplished that

this fusion of structures is unobtrusive. A free-standing bell tower, completed in the

1790s, was razed in the Soviet period (24).

The nearby Church of the Nativity of Christ shows similar decorative and structural

features, but its general appearance is quite different. Instead of the traditional five

cupolas with a bell tower in the west, the structure is highly centralized, with an

elongated series of octagons rising above the main structure in the manner of a spire. The

refectory and porch are modest in comparison with this soaring vertical emphasis. Of

special interest is the fact that this building, like a number of other eighteenth-century

masonry churches in Totma, was constructed in the two phases: the lower, winter church was

built in 1746-48, and the upper church was added in 1786-93. The lower church thus serves

as a base for the great height of the upper church; but the design is so accomplished that

this fusion of structures is unobtrusive. A free-standing bell tower, completed in the

1790s, was razed in the Soviet period (24).

Space does not permit a thorough analysis of the monuments in this once flourishing but

now distinctly provincial northern town. Among the best restored landmarks is the Church

of the Trinity in Green Fishers' Quarter, near the Sukhona River. Like the Nativity

Church, it was erected in two phases (1768-72 and 1780-88), with funds provided by the

merchant Sergei Cherepanov. The master builder was a certain Fedor Titov, a free peasant.

The church has since been restored to active use for the local Orthodox parish; its

cupolas are once again in place, and its whitewashed brick walls, with the distinctive

baroque scroll ornamentation of Totma's late eighteenth-century churches.

Space does not permit a thorough analysis of the monuments in this once flourishing but

now distinctly provincial northern town. Among the best restored landmarks is the Church

of the Trinity in Green Fishers' Quarter, near the Sukhona River. Like the Nativity

Church, it was erected in two phases (1768-72 and 1780-88), with funds provided by the

merchant Sergei Cherepanov. The master builder was a certain Fedor Titov, a free peasant.

The church has since been restored to active use for the local Orthodox parish; its

cupolas are once again in place, and its whitewashed brick walls, with the distinctive

baroque scroll ornamentation of Totma's late eighteenth-century churches.

And on the western fringes of Totma, there stands the

much-damaged but still imposing ensemble of the Savior-Sumorin Monastery, which played an

important role in the development of the town.  Founded in 1554 by Feodosii Sumorin, the monastery consisted

entirely of wooden structures until the latter part of the eighteenth century. Among its

surviving structures, the most significant is the palatial Ascension Cathedral, built and

expanded over a period of three decades, from 1796 to 1825. In its imposing late classical

forms, now abandoned and with its interior stripped, this church is reminiscent of ruined

nineteenth-century mansions in the southern part of the United States. Under current

circumstances, the restoration of these monumental structures is very much in question. Founded in 1554 by Feodosii Sumorin, the monastery consisted

entirely of wooden structures until the latter part of the eighteenth century. Among its

surviving structures, the most significant is the palatial Ascension Cathedral, built and

expanded over a period of three decades, from 1796 to 1825. In its imposing late classical

forms, now abandoned and with its interior stripped, this church is reminiscent of ruined

nineteenth-century mansions in the southern part of the United States. Under current

circumstances, the restoration of these monumental structures is very much in question.

The preceding survey has given a by no means complete view

of the remarkable variety of architectural monuments in the Vologda territory of northern

Russia. From the late fifteenth to the nineteenth century, this severe region provided the

resources for some of the most distinctive monuments in Russian architectural history,

including the medieval churches of the White Lake monasteries, the late medieval monuments

of Vologda, and the baroque churches of Velikii Ustiug and Totma. It must be noted that

this article has dealt only with masonry structures, yet the region was also once known

for its log architecture. Much has been lost over the past century to time and vandalism,

but until recently cities such as Vologda and Velikii Ustiug had retained a large number

of wooden houses. Yet, as noted in my preceding Visual Resources article on Vologda, the

surviving structures are increasingly under threat for lack of maintenance. Whether of

brick or wood, these monuments must be documented photographically, if they are to be

preserved for study and, one hopes, reclamation.

| ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS For assistance in preparing

the photographs in this article for publication, I would like to thank the Samuel H. Kress

Foundation. These photographs are a part of the William Brumfield collection at the

Photographic Archives of the National Gallery of Art, Washington. |

NOTES

1. A detailed study of the

architectural history of the St. Kirill and Ferapontov monasteries is contained in

I.A. Kochetkov, O.V. Leiekova, S.S. Pod"iapol'skii, Kirillo-Belozerskii i Ferapontov

monastyri: arkhitekturnye pamiatniki (Moscow, 1994).

2. Biographical information on St. Kirill

and other monastic leaders of the Belozersk region mentioned in this text is presented in

Prepodobnyi Kirill, Ferapont i Martinian Belozerskie (St. Petersburg, 1993), pp. 4-167.

3. On Italian influence in late fifteenth

and early sixteenth-century Muscovite architecture, see William Craft Brumfield, A History

of Russian Architecture (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993), pp. 92-106.

4. A sketch of Sergei Podiapolskii's

reconstruction of the original appearance of the Dormition Cathedral is contained in I.A.

Kochetkov, O.V. Leiekova, S.S. Pod"iapol'skii, Kirillo-Belozerskii monastyr'

(Leningrad, 1979), p. 40.

5. Pod"iapol'skii's reconstruction of

the original form of the Archangel Church is contained ibid., p. 41.

6. Attributions to Borisov are discussed in

Kochetkov, et al., Kirillo-Belozerskii i Ferapontov monastyri, pp. 27-28.

7. St. Ferapont (Therapontos) was born

Fedor Poskochin, another of Moscow's prominent noble families. An extensive published

history of the Ferapontov Monastery as a religious institution is Ivan Brilliantov,

Ferapontov Belozerskii Monastyr' (St. Petersburg, 1899), reprinted with an afterword by

Gerold Vzdornov (Moscow, 1994).

8. For examples of fifteenth-century Pskov

church architecture and decorative brickwork, see Brumfield, History, pp. 74-79.

9. For an account of the construction and

modification of the early monuments at Ferapontov Monastery, see V.D. Sarab'ianov,

"Istoriia arkhitekturnykh i khudozhestvennykh pamiatnikov Ferapontova

monastyria," Ferapontovskii sbornik: Vypusk vtoroi (Moscow, 1988), pp. 9-98.

10. On the frescoes by Dionisii and their

relation to the structure of the Nativity Cathedral, see V.N. Lazarev, Drevnerusskie

mozaiki i freski XI-XV vs. (Moscow, 1973), pp. 76-79, with plates 431-456; and Marina

Serebriakova (director of the Ferapontov museum), "Gimn Bogoroditse," Pamiatniki

otechestva, 30 (1993) 3-4: 109-117.

11. Material on the dates and construction

history of the Annunciation Church at Ferapontov Monastery is contained in Serebriakova,

"Pamiatniki arkhitektury Ferapontova monastyria," p. 194;

and V.D. Sarab'ianov, "Istoriia arkhitekturnykh i

khudozhestvennykh pamiatnikov Ferapontova monastyria," Ferapontovskii sbornik: Vypusk

tretii (Moscow, 1991), pp. 37-39.

12. On the Spas-Prilutskii Monastery, see

G. Bocharov and V. Vygolov, Vologda. Kirillov. Ferapontouo. Belozersk, (Moscow, 1979), pp.

127-51; and Geroi'd Vzdornov, Vologda (Leningrad, 1978), pp. 110-20. The second part of

its name derives from the monastery's location near a bend (luka) in the Vologda River.

13. On the St. Sophia Cathedral in

Vologda, see Brumfield, "Photographic Documentation of Architectural Monuments in the

Russian North: Vologda," Visual Resources, 12 (1996) 2: 136-139.

14. These construction dates for the

Annunciation Cathedral are given in G. Bocharov and V. Vygolov, Sol'vychegodsk. Velikii

Ustiug. Tot'ma (Moscow, 1983), pp. 24-27.

15. The name Ustiug means the "mouth

of the lug," and the epithet Velikii, or "great," was added at the end of

the sixteenth century to signify the city's importance as a commerical center. A detailed

survey of the medieval history of Velikii Ustiug is contained in V.P. Shil'nikovskaia,

Velikii Ustiug (razvitie arkhitektury goroda do serediny XIX v., (Moscow, 1973), pp. 8-26.

16. An analysis of the Dormition Cathedral

complex in Velikii Ustiug is presented in Bocharov and Vygolov, Sol'vychegodsk. Velikii

Ustiug. Tot'ma, pp. 92-117.

17. For a photograph of the St. Nicholas

church while still in use as a lumber mill, see P.A. Tel'tevskii, Velikii Ustiug (Moscow,

1977), p. 100.

18. There is no documentary evidence as to

the date of the founding of Trinity-Gleden Monastery, but it is clearly one of the

earliest monastic institutions in the north. For a discussion of possible dates, see

Shil'nikovskaia, Velikii Ustiug, pp. 113-14.

19. After the death of the first two brothers,

the third brother, Vasilii Grudtsyn, was left a bequest by his father-in-law, Filaret (who

had become an elder at the monastery) to complete the cathedral's construction. Vasilii

did not honor the agreement, and not until the hegumen of the monastery appealed to

Patriarch loakim in Moscow did Grudtsyn release the money for construction around 1690.

See Bocharov and Vygolov, Sol'vychegodsk. Velikii Ustiug. Tot'ma, pp. 249-50.

20. The design of the Archangel Michael

Cathedral in Ustiug is discussed in: Tel'tevskii, Velikii Ustiug, pp. 24-26; and Bocharov

and Vygolov, Sol'vychegodsk. Velikii Ustiug. Tot'ma, pp. 196-203.

21. Remarks on the iconography of the Trinity

Cathedral iconostasis and its relation to Western religious art are contained in K. Onash,

"Ikonostasy Velikogo Ustiuga," in V.A. Sablin, ed., Velikii Ustiug:

kraevedcheskii ai'manakh. Vol. 1 (Vologda, 1995): 180-194. Information on the identity of

the iconostasis masters (the carvers, the gilder, and the main icon painters) is contained

in Bocharov and Vygolov, Soi'vychegodsk. Velikii Ustiug. Tot'ma, pp. 255-57.

22. A survey of Kuskov's work in North

America is contained in N. A. Chernitsyn, "Issledovatel' Aliaski i Sevemoi Kalifornii

Ivan Kuskov," Letopis' Severn, vol. 3 (Moscow, 1962), pp. 108-21.

23. On the genesis of the Church of the

Entry into Jerusalem, see Bocharov and V. Vygolov, Sol'vychegodsk. Velikii Ustiug. Tot'ma,

p. 278.

24. Ibid., 281.

|

As the sixteenth century progressed the St. Kirill Belozerskii Monastery received major

donations that made it one of the largest such institutions in Russia, second in size only

to the Trinity-St. Sergius Monastery near Moscow. In 1519 the monastery refectory and its

attached Church of the Presentation of the Virgin were rebuilt in brick. The church itself

is situated at the eastern end of the refectory axis, with a polygonal east wall elevated

on a high socle and originally culminating in rows of kokoshniki, over which was a single

brick drum and cupola (

As the sixteenth century progressed the St. Kirill Belozerskii Monastery received major

donations that made it one of the largest such institutions in Russia, second in size only

to the Trinity-St. Sergius Monastery near Moscow. In 1519 the monastery refectory and its

attached Church of the Presentation of the Virgin were rebuilt in brick. The church itself

is situated at the eastern end of the refectory axis, with a polygonal east wall elevated

on a high socle and originally culminating in rows of kokoshniki, over which was a single

brick drum and cupola ( The second of the churches commissioned by Vasilii III at the monastery was dedicated to

John the Baptist. Also built in 1531-34, it shares certain stylistic features with the

Archangel Gabriel Church, including a roofline that originally culminated in kokoshniki (

The second of the churches commissioned by Vasilii III at the monastery was dedicated to

John the Baptist. Also built in 1531-34, it shares certain stylistic features with the

Archangel Gabriel Church, including a roofline that originally culminated in kokoshniki ( The monastery's first masonry structure, the brick Cathedral of the Nativity of the

Virgin, was built in 1490, six years earlier than the Dormition Cathedral at the St.

Kirill Monastery. Both churches share a relatively simple cross-inscribed plan, with four

piers and a single drum and cupola. The Nativity is smaller, but shows a greater

refinement of proportions, in part because of its elevation on a raised base, or podklet (

The monastery's first masonry structure, the brick Cathedral of the Nativity of the

Virgin, was built in 1490, six years earlier than the Dormition Cathedral at the St.

Kirill Monastery. Both churches share a relatively simple cross-inscribed plan, with four

piers and a single drum and cupola. The Nativity is smaller, but shows a greater

refinement of proportions, in part because of its elevation on a raised base, or podklet ( The west portal was framed with ogival perspective arches of molded brick and was

surrounded by frescoes devoted to the Nativity of the Virgin Mary. Although partially

damaged by the construction of the parvis in the sixteenth century, the frescoes were

afforded a greater measure of protection from the climate by that same construction, and

they have survived relatively intact. They are, in fact, excellent examples of the work of

one of the most important medieval Russian artists, Dionisii, who with the assistance of

his two sons painted the interior of the Nativity Cathedral in 1502

The west portal was framed with ogival perspective arches of molded brick and was

surrounded by frescoes devoted to the Nativity of the Virgin Mary. Although partially

damaged by the construction of the parvis in the sixteenth century, the frescoes were

afforded a greater measure of protection from the climate by that same construction, and

they have survived relatively intact. They are, in fact, excellent examples of the work of

one of the most important medieval Russian artists, Dionisii, who with the assistance of

his two sons painted the interior of the Nativity Cathedral in 1502  Due to the remote location of the small Ferapontov Monastery/ the frescoes on both

interior and exterior of the Nativity Cathedral were not frequently overpainted and are

relatively well preserved/ despite modifications to the structure of the church. These

changes include not only the addition of the parvis on the north/ west and south sides/

but also the construction of two attached churches: the Church of the Annunciation (1530

31; see below), and the Church of St. Martinian (1640), with its tent tower. On the west

side/ the ensemble is linked by a raised gallery/ which extends from the parvis to the

Annunciation Church/ with a seventeenth-century bell tower situated near the midpoint (

Due to the remote location of the small Ferapontov Monastery/ the frescoes on both

interior and exterior of the Nativity Cathedral were not frequently overpainted and are

relatively well preserved/ despite modifications to the structure of the church. These

changes include not only the addition of the parvis on the north/ west and south sides/

but also the construction of two attached churches: the Church of the Annunciation (1530

31; see below), and the Church of St. Martinian (1640), with its tent tower. On the west

side/ the ensemble is linked by a raised gallery/ which extends from the parvis to the

Annunciation Church/ with a seventeenth-century bell tower situated near the midpoint ( During the five decades after the completion of the three churches donated by Vasilii III

at the St. Kirill and Ferapontov Monasteries construction began on other masonry churches

throughout the Vologda and White Lake territories. In the immediate area of Vologda the

earliest significant masonry structure is the Cathedral of the Savior at the

Savior-Prilutskii Monastery. Established in 1371, the Savior-Prilutskii Monastery was

supported by Moscow's grand prince Dmitrii Ivanovich (Donskoi) as one of the first

bulwarks of Orthodox Moscow in the rich but difficult terrain surrounding Vologda

During the five decades after the completion of the three churches donated by Vasilii III

at the St. Kirill and Ferapontov Monasteries construction began on other masonry churches

throughout the Vologda and White Lake territories. In the immediate area of Vologda the

earliest significant masonry structure is the Cathedral of the Savior at the

Savior-Prilutskii Monastery. Established in 1371, the Savior-Prilutskii Monastery was

supported by Moscow's grand prince Dmitrii Ivanovich (Donskoi) as one of the first

bulwarks of Orthodox Moscow in the rich but difficult terrain surrounding Vologda  The cathedral walls support two rows of curved structural gables, or zakomary, leading to

a clearly spaced ensemble of five drums and cupolas. The upper parts of the drums show

ornamental brickwork in the Pskov style, which had been assimilated throughout Muscovy in

the fifteenth century, although not in the Kremlin cathedrals. The main cupola, much

larger than the flanking four, creates a strong vertical point to the pyramidal shape. The

height of the structure is increased by a podklet, or socle, which contained a separate

church for use primarily in the winter (a feature typical of Muscovite churches). The

interior of the Savior Cathedral, whose white-washed walls were never painted with

frescoes, possesses an austere monumentality displayed in the ascent from the four piers

to the corbelled, vaults (reflected in the exterior zakomary) that support the cupola

drums. The vaulting is reinforced with iron tie rods. A raised gallery attached to the

north, west, and south facades leads on the southeast corner to a refectory and Church of

the Presentation, built in the late 1540s in a style similar to the refectory churches at

St. Kirill and Ferapontov monasteries, with a roof of decorative kokoshniki ascending to a

single cupola. The ensemble is completed by a bell tower, rebuilt in 1729-30 on a

seventeenth-century base.

The cathedral walls support two rows of curved structural gables, or zakomary, leading to

a clearly spaced ensemble of five drums and cupolas. The upper parts of the drums show

ornamental brickwork in the Pskov style, which had been assimilated throughout Muscovy in

the fifteenth century, although not in the Kremlin cathedrals. The main cupola, much

larger than the flanking four, creates a strong vertical point to the pyramidal shape. The

height of the structure is increased by a podklet, or socle, which contained a separate

church for use primarily in the winter (a feature typical of Muscovite churches). The

interior of the Savior Cathedral, whose white-washed walls were never painted with

frescoes, possesses an austere monumentality displayed in the ascent from the four piers

to the corbelled, vaults (reflected in the exterior zakomary) that support the cupola

drums. The vaulting is reinforced with iron tie rods. A raised gallery attached to the

north, west, and south facades leads on the southeast corner to a refectory and Church of

the Presentation, built in the late 1540s in a style similar to the refectory churches at

St. Kirill and Ferapontov monasteries, with a roof of decorative kokoshniki ascending to a

single cupola. The ensemble is completed by a bell tower, rebuilt in 1729-30 on a

seventeenth-century base. The line of development represented by the three main monastery churches-(in Russian,

sobor, or "cathedral")-discussed above would lead to the Cathedral of St. Sophia

in Vologda, built in 1568-70 to a design based on the Dormition Cathedral in the Moscow

Kremlin

The line of development represented by the three main monastery churches-(in Russian,

sobor, or "cathedral")-discussed above would lead to the Cathedral of St. Sophia

in Vologda, built in 1568-70 to a design based on the Dormition Cathedral in the Moscow

Kremlin  Like most northern towns, Ustiug was built almost entirely of wood, and fire was a

constant menace. As a result there are no surviving churches before the middle of the

seventeenth century. As trade with western Europe expanded in the seventeenth century,

Ustiug's merchants and churches acquired wealth that created some of the town's early

brick churches. The main cathedral, dedicated to the Dormition of Mary, was built in brick

during the 1550s, but had to be rebuilt a century later, after a major fire damaged the

walls. Funds to complete the reconstruction were provided by Tsar Aleksei Mikhailovich and

by the Bosykh family, local merchants of considerable wealth. In the eighteenth century,

the cathedral was modified still further. It is now flanked by three other churches, of

which the most impressive is the Cathedral of St. Procopius of Ustiug, built in 1668

Like most northern towns, Ustiug was built almost entirely of wood, and fire was a

constant menace. As a result there are no surviving churches before the middle of the

seventeenth century. As trade with western Europe expanded in the seventeenth century,

Ustiug's merchants and churches acquired wealth that created some of the town's early

brick churches. The main cathedral, dedicated to the Dormition of Mary, was built in brick

during the 1550s, but had to be rebuilt a century later, after a major fire damaged the

walls. Funds to complete the reconstruction were provided by Tsar Aleksei Mikhailovich and

by the Bosykh family, local merchants of considerable wealth. In the eighteenth century,

the cathedral was modified still further. It is now flanked by three other churches, of

which the most impressive is the Cathedral of St. Procopius of Ustiug, built in 1668  Despite the current difficult economic situation, progress in preserving the historic

architecture of Ustiug is clearly visible. The oldest structure to survive in its original

form is the Church of the Ascension, built in 1648-49 in the style of a Moscow parish

church, with a highly ornamented, asymmetrical grouping of volumes. The Church of St.

Nicholas Gostunskii (late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries), with its remarkable

detached bell tower, shows a greater precision of form. The low-relief, scrolled baroque

ornament on the tower is traced in black in a manner reminiscent of the town's most famous

craft technique-niello. Two decades ago this church was still being used as a saw mill

because of its location on the bank of the Sukhona River. It has since been restored on

the exterior, and is now used as a gallery to display the work of local painters

Despite the current difficult economic situation, progress in preserving the historic

architecture of Ustiug is clearly visible. The oldest structure to survive in its original

form is the Church of the Ascension, built in 1648-49 in the style of a Moscow parish

church, with a highly ornamented, asymmetrical grouping of volumes. The Church of St.

Nicholas Gostunskii (late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries), with its remarkable

detached bell tower, shows a greater precision of form. The low-relief, scrolled baroque

ornament on the tower is traced in black in a manner reminiscent of the town's most famous

craft technique-niello. Two decades ago this church was still being used as a saw mill

because of its location on the bank of the Sukhona River. It has since been restored on

the exterior, and is now used as a gallery to display the work of local painters

Further

to the south along the Sukhona is the late baroque Church of St. Simeon the Stylite

(1760s), which also has a large, free-standing bell tower near its northwest corner. The

design of the church is heavily derived from Petersburg architecture of the reign of

empress Elizabeth. Like much of the central part of Ustiug, the west facade of this church

forms a picturesque silhouette when seen from the river. The eastern approach, however,

has an appearance of its own, with lanes that wander between small wooden houses and

gardens. In such areas one has a sense of what the town might have looked like in the

eighteenth century.

Further

to the south along the Sukhona is the late baroque Church of St. Simeon the Stylite

(1760s), which also has a large, free-standing bell tower near its northwest corner. The

design of the church is heavily derived from Petersburg architecture of the reign of

empress Elizabeth. Like much of the central part of Ustiug, the west facade of this church

forms a picturesque silhouette when seen from the river. The eastern approach, however,

has an appearance of its own, with lanes that wander between small wooden houses and

gardens. In such areas one has a sense of what the town might have looked like in the

eighteenth century. Although the development of St. Petersburg in the eighteenth century lessened the

importance of Ustiug as a center of transportation and trade, it continued to prosper as a

mercantile center and became renowned as a center of crafts such as leather and metal

working, as well as the production of fine enamel objects. In particular its silversmiths

developed special skills in the niello technique, and their work was in demand not only in

the north but in St. Petersburg and the imperial court. Although never a major city,

Ustiug's prosperity was reflected in the increasing number of its masonry houses, a number

of which have been preserved along the river embankment and along Uspenskaia (Dormition)

Street, roughly parallel to the river.

Although the development of St. Petersburg in the eighteenth century lessened the

importance of Ustiug as a center of transportation and trade, it continued to prosper as a

mercantile center and became renowned as a center of crafts such as leather and metal

working, as well as the production of fine enamel objects. In particular its silversmiths

developed special skills in the niello technique, and their work was in demand not only in

the north but in St. Petersburg and the imperial court. Although never a major city,

Ustiug's prosperity was reflected in the increasing number of its masonry houses, a number

of which have been preserved along the river embankment and along Uspenskaia (Dormition)

Street, roughly parallel to the river.

The wealth of local

merchants led to yet another series of donations to monastery churches, some of which

gained elaborate gilded iconostases that reveal a northern interpretation of European

baroque art. One of the best examples is Trinity Cathedral at the Trinity-Gleden

Monastery. Although visible from Velikii Ustiug, the monastery is situated some five

kilometers to the southwest on the opposite bank of the Sukhona. Established no later than

the middle of the thirteenth century, the monastery consisted entirely of wooden

structures, including three log churches, for the first four centuries of its existence

The wealth of local

merchants led to yet another series of donations to monastery churches, some of which

gained elaborate gilded iconostases that reveal a northern interpretation of European

baroque art. One of the best examples is Trinity Cathedral at the Trinity-Gleden

Monastery. Although visible from Velikii Ustiug, the monastery is situated some five

kilometers to the southwest on the opposite bank of the Sukhona. Established no later than

the middle of the thirteenth century, the monastery consisted entirely of wooden

structures, including three log churches, for the first four centuries of its existence  The cathedral's design and exterior form owe much to the slightly earlier Cathedral of the

Archangel Michael (1653-56) at the monastery of the same name in Ustiug itself. Both are

elevated on a high socle or base; both have walls that rise to a cornice underlying the

curved gable ends, or zakomary (a distant derivation from early Italian influence, such as

the Archangel Michael Cathedral in the Moscow Kremlin); and each has a level, four-sloped

roof placed over the zakomary (as opposed to a roofline following the contours of the

curved gables)

The cathedral's design and exterior form owe much to the slightly earlier Cathedral of the

Archangel Michael (1653-56) at the monastery of the same name in Ustiug itself. Both are

elevated on a high socle or base; both have walls that rise to a cornice underlying the

curved gable ends, or zakomary (a distant derivation from early Italian influence, such as

the Archangel Michael Cathedral in the Moscow Kremlin); and each has a level, four-sloped

roof placed over the zakomary (as opposed to a roofline following the contours of the

curved gables)  Taken together, these factors permit a greater natural illumination of the interior of the

Trinity Cathedral and its iconostasis, which is one of the most elaborate in the Russian

north. It should be noted that the interior walls of the cathedral were not painted with

frescoes and the main icon screen, consisting of five rows of intricately carved, gilded

wood, was erected only in 1776-84. In a departure from typical practice, the iconostasis

contains extensive statuary that amplifies the central iconic motif of the ministry and

Passion of Christ. The ultimate sources for this peculiar eighteenth-century combination

of florid baroque and neoclassical elements are St. Petersburg and, possibly, the